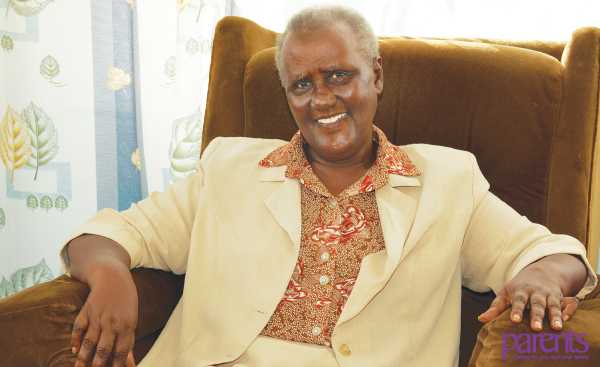

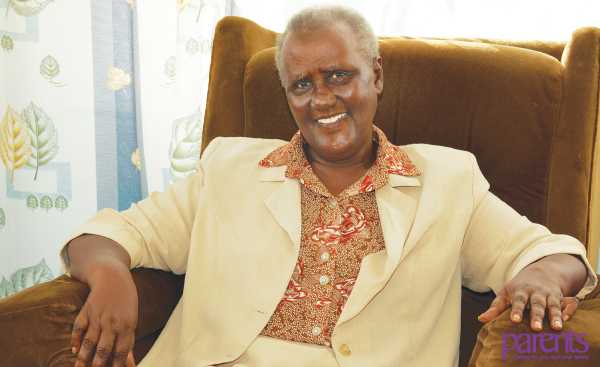

PROF ROSALIND MUTUA Outstanding contribution to education

In 2002 Professor Rosalind Mutua became the first vice chancellor of Kiriri Women’s University of Science and Technology, a private women-only university in Kenya. Now retired, the 74-year-old professor walks

In 2002 Professor Rosalind Mutua became the first vice chancellor of Kiriri Women’s University of Science and Technology, a private women-only university in Kenya. Now retired, the 74-year-old professor walks ESTHER KIRAGU through her rich contribution to the education sector and her influence in empowering women through science and technology.

When I travelled to Professor Mutua’s home in Mwala, Machakos County, for this interview, I found her engrossed in a book. It is clear she holds knowledge in high esteem. It is this keen interest that has seen her take deliberate steps to pave way for women to study science and technology. So when Kiriri Women’s University of Science and Technology (KWUST) opened its doors in September 2002, who would be its pioneer vice chancellor other than Prof Mutua?

A passion for girl-child education…

The university wanted to challenge the generations of gender stereotyping and a deep-rooted culture that favoured males at all levels of education. “At the time, research had shown that female students comprised of a mere 20 per cent of Kenya’s university student population. Among these, less than one-fifth were enrolled in science-based courses. We wanted to do something to change these statistics,” Prof Mutua explains.

The university understood that the best way to bridge the gender gap was to have more females enroll in science and technology courses such as mathematics, computer science and ICT (information, communication and technology). The institution offered computer and environmental science as well as electrical engineering courses. Prof Mutua says, “Women have the potential to perform as well as their male counterparts in scientific fields if they are given a conducive environment to study.”

As a mother and a woman, she understood the plight of female students only too well. She grew up in a farm in the African reserve areas near Mount Kenya during the colonial era. And at a time when there wasn’t much emphasis on girl-child education, she worked through eight years of primary and intermediate education and made it to a national school – African Girls High School now Alliance Girls High School.

“There were very few girls’ secondary schools during my days. In addition, those who proceeded to institutions of higher learning had limited options, as they basically had to choose between nursing and teaching careers. Further, unlike today, we had no career fairs to help one explore a variety of career opportunities,” she explains.

Prof Mutua overcame these challenges and excelled well to gain admission to the University of Nairobi in 1963 to study for a Bachelor of Arts in English and history. After her training, she got married to the late David Wambua Mutua. “I met David at the University of Nairobi, and it was love at first sight,” she says. Sadly, David passed on in 1989 after a long illness, leaving behind their two children – Ben Masaku and Angela Mwikali, both of who are now grown-up and married.

“David’s death marked the most painful time of my life, as he was a great husband and father to our two children. We fondly remember him and thank God for giving us such a friend, father and husband,” says Prof Mutua who has three grandchildren; Denis, Kevin and Kayla.

Leaving her mark in the education sector…

Prof Mutua carved her career path in the education sector beginning as an assistant secretary at the East African Community in Nairobi where she worked for two years before joining the Ministry of Education as an education officer. She says although she loved her job, at some point, she was dissatisfied with the monotony that sometimes comes with doing administrative-related duties. As such, she enrolled at the University of Nairobi for her Masters degree in 1971. Two years later, she plunged into lecturing starting as a tutorial fellow at the University of Nairobi before moving to Kenyatta University where she rose through the ranks to become a senior lecturer.

A lover of acquisition of knowledge, Prof Mutua aspired for more education and attained a PhD in education planning and administration.

This came in handy, as she was then a director of the African Center Curriculum Development at Kenyatta University in 1984. She went on to become deputy principal of Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT) in 1990.

When Prof Mutua was named deputy vice-chancellor in charge of Research, Production and Extension at JKUAT in 1995, many wondered how she found herself in an engineering and agricultural-oriented university with her background in humanities. “At the time, I was the only senior administrator who was in humanities; all the others were scientists, engineers mathematicians or science-based professors,” she says but this did not intimidate her.

She proved her worth and was successful in changing the mindset that scientists had that they couldn’t learn anything from humanities. “For instance, an engineer would wonder why he needed business skills, yet stories abound of graduates of science-based courses who were tarmacking and frustrated by fruitless job hunts but they couldn’t think of how to turn their knowledge and skills into a business to become self-employed and create employment for more people,” she explains. This became her biggest goal and one of the things she is proud of was pioneering the School of Business offering business-related courses at JKUAT. Today she is happy to note that there are many professionals who are turning to self-employment and hopes this will result into an increase of innovators in the country.

She also served as the vice-chair of Commission for Higher Education, now Commission for University Education, a body charged with accrediting initially private universities in the country. Here, she would help formulate policies that shaped higher education in Kenya.

Her keen interest in promoting women’s education saw her join the Forum for African Women Educationalists (FAWE), a Pan-African non-governmental organisation to promote girls’ and women’s education in sub-Saharan Africa in line with education for all. And when a chance to run Kiriri Women’s University of Science and Technology came up just after she had retired from JKUAT in 2002, she grabbed it with both hands.

“Kiriri in Kikuyu means the girl’s bedroom and boys are not allowed to enter it. The university provided a shield for the female students where especially those who were shy could perform at their best. And they did,” she explains.

But she admits that running a women-only university from scratch in the field of science and technology was no mean feat. She and others had to do a vigorous campaign to encourage parents to allow their daughters, some of who had scored well in KCSE but were reluctant to pursue science-based courses to join KWUST. She served for one five-year term before retiring in 2007 to do farming in Mwala, Machakos County. Prof Mutua is contented with the contribution she has made in the education industry and hopes those who have come after her can take the industry to the next level.

Her take on parenting today…

With regard to parenting today, Prof Mutua says, “I get very worried about parenting today as many parents seem to have abdicated their parenting role to everyone else but themselves – househelps, television, teachers just to name but a few. Life seems to be so busy that parents are at work most of the time and therefore they leave their children to house managers and also enroll children to day care centers at a very young age.” She adds that parents barely have any time to spend with their children these days.

Prof Mutua reckons that it is more important to live rather than to make a living because as a parent, you can provide everything that money can buy but the most important thing is your presence, as money cannot compensate for a parent’s absence from home.

In her opinion, society has played a role in the increase of broken homes that we witness today. Very few Kenyan couples can afford only one income not even the middle class and therefore it is important for the government to provide a system that gives enough time to look after children until they are of school-going age and then the mother especially can go back to work. Otherwise the society will have young people who have no knowledge of their parents.

As we conclude this interview, the professor says, “I hope that today, every woman is taking advantage of the massive opportunities available to pursue courses of their choice and venture into their preferred careers. In addition, with the many female role models to look up to, women have every reason to scale the ladders of education and career, and succeed.”

Published April 2016